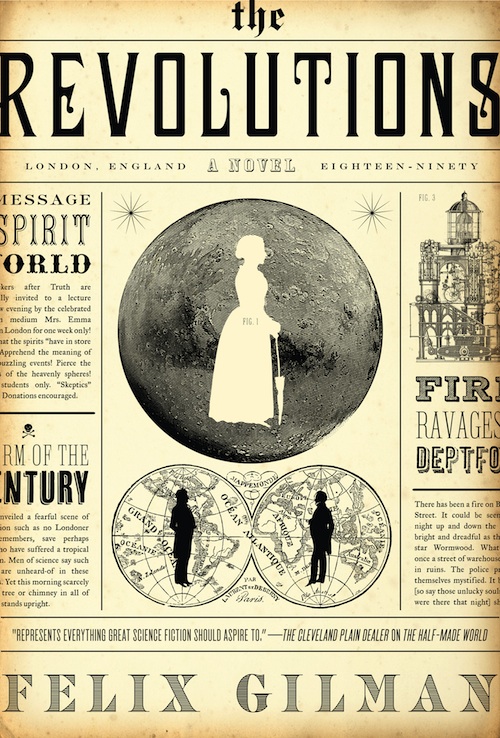

Check out The Revolutions, Felix Gilman’s tale of Victorian science fiction, arcane exploration, and planetary romance. Read an excerpt below and get the book March 1st from Tor Books!

In 1893, young journalist Arthur Shaw is at work in the British Museum Reading Room when the Great Storm hits London, wreaking unprecedented damage. In its aftermath, Arthur’s newspaper closes, owing him money, and all his debts come due at once.

His fiancé Josephine takes a job as a stenographer for some of the fashionable spiritualist and occult societies of fin de siècle London society. At one of her meetings, Arthur is given a job lead for what seems to be accounting work, but at a salary many times what any clerk could expect. The work is long and peculiar, as the workers spend all day performing unnerving calculations that make them hallucinate or even go mad, but the money is compelling…

Chapter One

It was the evening of what would later be called the Great Storm of ’93, and Arthur Archibald Shaw sat at his usual desk in the Reading Room of the British Museum, yawning and toying with his pen. Soft rain pattered on the dome. Lamps overhead shone through a haze of golden dust. Arthur yawned. There was a snorer at the desk opposite, head back and mouth open. Two women nearby whispered to each other in French. Carts creaked down the aisle, the faint tremors of their passing threatening to topple the tower of books on Arthur’s desk, which concerned explosives, and poisons, and exotic methods of murder.

He was writing a detective story. This was something of an experiment. Not knowing quite how to start, he’d begun at the end, which went:

That night the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral broke through London’s black clouds as if it were the white head of Leviathan rising from the ocean. The spire and the cross shone in a cold and quite un-Christian moonlight, and diabolical laughter echoed through the night. The detective and his quarry stood atop the dome, beneath the spire, each man ragged from the exertion of their chase.

“Stop there, Vane,” the detective called; but Professor Vane only laughed again, and began to climb the spire. And so Dr Syme pursued.

Which was not all bad, in Arthur’s opinion. The important thing was to move quickly. It was only that month that Dr Conan Doyle had sent his famous detective off into the great beyond—chucking him unceremoniously from a waterfall in Switzerland—and the news that there would be no more stories of the Baker Street genius had thrown London’s publishing world into something of a panic. In fact, there were nearly riots, and some disturbed individuals had threatened to torch the offices of the Strand Magazine. The hero’s death left a gap in the firmament. The fellow who was first to fill it might make a fortune. It was probably already too late.

For the past two and a half years Arthur had been employed by The Monthly Mammoth to write on the subject of the Very Latest Scientific Advances. He wasn’t any kind of scientist himself, but nobody seemed to mind. He wrote about dinosaurs, and steam engines, and rubber, and the laying of transatlantic telegraph cables; or how telephones worked; or the new American elevators at the Savoy; or whether there was air on the moon; or where precisely in South America to observe the perturbations of Venus; or whether the crooked lines astronomers saw on the fourth planet might be canals, or railroads, or other signs of civilization—and so on. Not a bad job, in its way—there were certainly worse—but the Mammoth paid little, and late, and there was no prospect of advancement there. Therefore he’d invented Dr Cephias Syme: detective, astronomer, mountain-climber, world-traveller, occasional swordsman, et cetera.

Vane dangled by one hand from the golden cross, laughing, his white hair blowing in the wind. With the other hand he produced a pistol from his coat and pointed it at Syme.

“What brought you here, Syme?”

The Professor appeared to expect an answer. Since Dr Syme saw no place to take shelter, he began to explain the whole story—the process by which, according to his usual method, he had tackled each part of Vane’s wild scheme—how he had ascended that mountain of horrors—from the poisoning at the Café de L’Europe, to the cipher in the newspaper advertisements that led to the uncovering of the anarchists in Deptford, which in turn led to the something or other by some means, and so on, and thus to the discovery of the bomb beneath Her Highness’s coach, and thus inevitably here, to the Cathedral.

Arthur sketched absent-mindedly on his blotting paper: a dome, a cross, inky scudding clouds.

The notion of the struggle on the dome had come to him in a dream, just two nights ago; it had impressed itself upon him with the intensity of a lightning flash. Unfortunately, all else remained dark. How did his detective get there? How precisely had they ascended the dome (was it possible?). And above all: what happened next?

Nothing, perhaps. In his dream, Dr Syme fell, toppling from the dome into black fog, nothing but hard London streets below. Not the best way to start a detective’s adventures. Something would have to be done about that. Perhaps he could have poor Syme solve his subsequent cases from the afterlife, through the aid of a medium.

Dr Syme lunged, knocking the pistol from the Professor’s grip, but his enemy swung away, laughing, and drew from his coat a new weapon: a watch.

“We have time,” the Professor said. “Dr Syme, I confess I have arranged events so that we might have time and solitude to speak. I have always felt that you, as a man of science, might see the urgent need for reform—for certain sacrifices to be made—”

Arthur’s neighbour began to pack his day’s writings into his briefcase. This fellow—name unknown—was stand-offish, thin, spectacled. Judging from the pile of books on his desk, on which words like clairvoyance and Osiris were among the most intelligible, his interests tended to the occult. He closed his briefcase, stood, swayed, then sat back with a thump and lowered his head to his desk. Arthur sympathised. The dread hour and its inexorable approach! Soon the warders would come around, waking up the sleepers, emptying out the room, driving Arthur, and Arthur’s neighbour, and the French women, and all the scholars and idlers alike out to face the night, and the rain, and the wind that rattled the glass overhead.

Midnight! The Professor waited, as if listening for some news to erupt from the befogged city below.

“Well,” Syme said. “I dare say I know your habits after all this time. I know how you like to do things in twos. I knew there would be a second bomb. At the nave, was it, or the altar? I expect Inspector Wright’s boys found it quick enough—”

A terrible change came across the Professor’s face. All trace of civilization vanished, and savagery took its place—or, rather, not savagery, but that pure malignancy that only the refined intellect is capable of.

Howling, the Professor let go of the cross and flung himself onto Dr Syme.

Pens scratching away. Rain drumming on the glass, loudly now. A row of women industriously translating Russian into English, or English into Sanskrit, Italian into French. Arthur’s neighbour appeared to have fallen asleep.

Arm in arm, locked together in deathly struggle, the two men fell—rolling down the side of the dome—toward

Toward what, indeed!

“By God,” said Inspector Wright, hearing the terrible crash. He came running out into the street, to see, side by side, dead, upon the ground—

Arthur put down his pen, and scratched thoughtfully at his beard.

His neighbour moaned slightly, as if something were causing him pain. Concerned, Arthur poked his shoulder.

The man jumped to his feet, staring about in wild-eyed confusion; then he snatched up his briefcase and left in such a hurry that scholars all along the rows of the Reading Room looked up and tut-tutted at him.

Rain sluiced noisily down the glass. Lamps swayed in mid-air. Thunder reverberated under the dome as the Reading Room emptied out.

Arthur’d thought he might try to bring out his friend Heath for dinner, or possibly Waugh, but neither was likely to venture out in that weather. Bad timing and bloody awful luck.

He collected his hat, coat, and umbrella. These items were just barely up to the Reading Room’s standards of respectability, and he doubted that they were equal to the challenge of the weather outside. Certainly the manuscript of Dr Syme’s First Case was not—he’d left it folded into the pages of a treatise on poisons.

Outside a small band of scholars, idlers, and policemen sheltered beneath the colonnade. Beyond the colossal white columns, the courtyard was dark and the rain swirled almost sideways. In amongst it were stones, mud, leaves, tiles, newspapers, and flower-pots. Some unfortunate fellow’s sandwich-board toppled end-over-end across the yard, caught flight, and vanished in the thrashing air. Arthur’s hat went after it. It was like nothing he’d ever seen. A tropical monsoon, or whirlwind, or some such thing.

He was suddenly quite unaccountably afraid. It was what one might call an animal instinct, or an intuition. Later—much later—the members of the Company of the Spheres would tell him that he was sensitive, and he’d think back to the night of the Great Storm and wonder if he’d sensed, even then, what was behind it. Perhaps. On the other hand, anyone can be spooked by lightning.

He was out past the gates, into the street, and leaning forward into the wind, homewards down Great Russell Street, before he’d quite noticed that he’d left the safety of the colonnade. When he turned back to get his bearings, the rain was so thick he could hardly see a thing. The Museum was a faint haze of light under a black dome; its columns were distant white giants, lumbering off into the sea. The familiar scene was rendered utterly alien; for all he could tell, he might not have been in London any more, but whisked away to the Moon.

His umbrella tore free of his grip and took flight. He watched it follow his hat away over the rooftops, flapping like some awful black pterodactyl between craggy, suddenly lightning-lit chimneys, then off who-knowswhere across London.

Chapter Two

In a quiet Mayfair drawing-room, a man and a woman sat stiffly upright, eyes closed and hands outstretched across a white table-cloth. The curtains were drawn. A single candle on a rococo mantelpiece illuminated a circle of midnight-blue wallpaper, a row of photographs, and a rather hideous painting of the Titan Saturn devouring his children. There was a faint scent of incense.

The woman was middle-aged. She wore high-collared black and silver, and an expression of fierce resolution. The man was young and handsome, fair and blue-eyed, and faintly smiling. He was the subject of most of the photographs on the mantelpiece, posing stiffly, dressed for tennis or mountaineering or camel-riding.

On the table there was a large white card with a red sphere painted on it; they rested their fingers on its corners.

They sat all evening in silence, hardly even breathing, until at the same moment they each opened their eyes in alarm, jerking back their hands so violently that they sent the card spinning off the table into the dark.

The man swore, got to his feet, and went in search of it.

The woman clutched her necklace. “Mercury—what happened?”

He went by the name Mercury when they met. She went by Jupiter.

“A rude interruption.”

“Rudeness! I call it an assault. They struck us.”

“I suppose they did. Yes. Where did it go, do you suppose?”

“We were further than ever before. I saw the gate open before me—the ring turning—did you see it too?”

“Perhaps.”

“Then a terrible discord. And shaking, as if the spheres themselves halted in their motions—how?” She took a deep breath, collected herself, and stood.

He crouched. “Aha. It slid under the wardrobe—and that hasn’t moved since my father’s day. Bloody nuisance.”

“They struck at us, though we were far out.”

“They did, didn’t they? Troubling. I thought we had more time.”

She glared at him. “Your father’s friends, Atwood?”

Martin Atwood was his real name, and this was his house. He stood. “Well, don’t blame me.”

“No? Then who should I blame?”

“I expect we’ll find out soon enough. I wonder how they did it? I wonder what they did? Something dreadful, no doubt. Wouldn’t that be just like them?”

He lit a lamp, and snuffed the candle.

“If only we knew who they were,” he said.

There was the sound of rain at the window, first a whisper, then a clattering, thrashing din.

“Aha,” he said. “See? Something dreadful.”

Over the noise of the storm there was the shrill insistent ring of the telephone across the hall. Atwood poured himself a drink before answering.

The storm smashed a fortune in window glass. It uprooted centuryold trees. It sank boats and toppled cranes. It washed up things from the bottom of the river, rusted and rotten stuff, yesterday’s rubbish and artifacts older than the Romans. It vandalised the docks at St. Katharine’s. It flooded streets and houses and cellars and the Underground. It deposited chimneys on unfamiliar roofs, laundry in other peoples’ gardens, dead dogs where they weren’t wanted. It cracked the dome of the Reading Room and let in the rain. It coated the fine marble facades of Whitehall with river muck. Lightning struck Nelson’s Column, scattering the few dozen unfortunate souls who slept at its foot like so many wet leaves. The lights along the Embankment whipped free and floated downriver. The London Electric Supply Corporation’s central station at Deptford flooded and went dark. Barometers everywhere were caught unawares. Omnibuses slewed like storm-tossed ships, trams detailed, horses broke their legs. Men died venturing out after stalls, carts, pigeons, and other items of vanishing property.

Arthur Archibald Shaw staggered and slid from shelter to shelter. An abandoned bus in the middle of Southampton Row gave him protection from the wind. God only knew what had become of the horses. An advertisement on the side for something called KOKO FOR HAIR took on a fearful pagan quality. What dreadful god of the storm was Koko? He stumbled on, clutching at lampposts, and turned the street corner (by now quite lost) just as lightning flashed and snapped a tree in two. He stopped in a doorway and watched leaves and roof tiles whip past. Someone’s house. A light in the window. He could expect no Christian charity on a night like this. A horse ran down the street before him, wide-eyed and panicking.

He shivered, wrapped his arms around himself, stamped his feet. He was young, and he was big—running to fat, his friend Waugh liked to say. Well, thank God for every pound and ounce. Skinny little Waugh would have been airborne half a mile ago.

The storm appeared to have engulfed all of London. Lightning overhead flashed signals, directing coal-black hurrying clouds to their business in all quarters of the city.

His fear was mostly gone; what had taken its place was excitement, accompanied by a nagging anxiety over the cost of replacing his hat and umbrella. He wondered if he might defray the expense by selling an account of the storm to the Mammoth—he was already thinking of it as The Storm of ’93—or, better yet, the New York periodicals: Our correspondent in London. Monsoon in Bloomsbury. Typhoon on the Thames. An Odyssey, across the city, or at least across the mile between the Museum and home. They’d like the panicked horse—it would make a good picture.

He peered back south in the direction the horse had fled. Behind the rooftops and out over the river there was something like a black pillar of cloud. It resembled a gigantic screw bolting London to the heavens, turning tighter and tighter, bringing the sky down. Behind it there was an unpleasant reddish light.

The Isle of Dogs and the West India Docks suffered the worst of it. For years afterwards, those who’d seen the Storm, and those who hadn’t, but remembered it as if they had, spoke of crashing waves; the lights of troubled boats swinging crazily in the dark, and then, dreadfully, going out; and bells ringing, and thunder, and timbers creaking, and chains snapping, and cranes falling, and men screaming as the waves swept them off the docks and downriver, perhaps all the way to the sea.

What wasn’t much remarked on was that the Storm also flooded Norman Gracewell’s Engine—for the simple reason that few people who didn’t have business with the Engine knew it was there. Mr Dimmick kept away sneaks and snoops—he was better than a guard-dog, Gracewell liked to say. But there was nothing Dimmick could do to keep out the flood waters. The Engine was mostly underground, which had seemed, when the Company built the thing, like a good way to ensure secrecy, but now ensured that the flood quickly filled all the Engine’s rooms. Most of the workers fled before the flooding got too severe, abandoning their desks and their ledgers; but Gracewell himself remained until the last minute, pacing back and forth in his office, shouting into a telephone, demanding an explanation, demanding more time and more money, demanding an accounting for this outrage, long after the flood had severed the wires and the line had gone dead.

Arthur lived in a small flat on the end of Rugby Street. Under ordinary circumstances it was a short walk from the Museum, but that night it took an hour, and by the time he approached home he’d had more than enough weather to last him a lifetime.

Through the rain he saw Mr Borel’s stationery shop on the corner. He knew the shop well—he often bought ink and tobacco and newspapers there. In fact, he owed Borel a moderate sum of money. The place was in a sorry state: the sign was askew, the windows had shattered in two or three places, and the door swung open. There was usually a bright blueand-yellow sign over a basement office that read J.E. BRADMAN, STENOGRAPHY, TYPEWRITING & TRANSLATIONS, but that was gone, too, ripped off its hinges and blown God knows where. Poor old Borel and poor old Mr Bradman whoever he was.

Someone inside—a girl—screamed.

Arthur abandoned caution and ran headlong across the street, sliding and stumbling in the wind, and in through the door. Lightning flashed behind him. When his vision cleared he saw Mr Borel’s daughter, Sophia, standing behind the counter, screaming. Her father stood in a puddle, holding a broom. An eel flopped at his feet. Sophia stared at it in horror, as if were a vampire that had broken into her bedroom. It was, no denying it, hideous.

A young woman Arthur had never seen before held a candle, inspecting the eel with a mixture of curiosity and distaste. Her hair was tangled and her dress dishevelled, as if she’d dressed in a hurry. She looked up at Arthur in surprise.

“Hello,” she said. “Are you all right?”

“Yes. As well as can be expected. There was—I heard screaming.”

“It was a very heroic entrance. I’m sorry—it was! Sophia cried out—well, you can hardly blame her—it’s a frightful-looking monster, poor thing.”

Strikingly green eyes, he noticed; emerald-like by candlelight. A quick, pleasing face.

He straightened his coat, wiped twigs and leaves from his hair.

“So I see,” he said.

“Are you hurt?”

There was blood on the hand that had wiped his hair, but not a great deal. His head stung a little, now that he noticed it.

“Not at all,” he said. “Could be worse, anyway.”

She looked out the open door behind him and shuddered.

Arthur shrugged off his overcoat. In its current state it would hardly be gallant to offer it to her. She’d be better off without it.

“Mr Shaw,” Borel said. The eel snapped at his broom.

Borel’s shop was a long way from the river or any fish-market that Arthur knew of, and the eel’s presence was a small mystery. He’d heard of hurricanes blowing things all over the place in the sort of places that had hurricanes, but one didn’t expect it in London. No doubt it was even more puzzling to the eel.

“Hello, Mr Borel. Is everything all right?”

It quite plainly wasn’t. The door had blown open, shelves had fallen, and Borel’s stock was soaked. Tins of tobacco and creams and medicines lay scattered on the floor. The wind and the rain had made sad heaps out of German newspapers, French photographs of dancing girls, and the magazines of various obscure trades. Arthur realised that he was standing on a ruined copy of the Metropolitan Dairyman.

“By God. It’s extraordinary out there. Extraordinary. You’d think you were in the tropics. I lost my umbrella. There was a horse.”

He closed the door. The wind opened it again. He sat on the floor with his back against it.

The eel thrashed. It appeared to be getting weaker. Borel poked it again.

The green-eyed woman said, “Your coat.”

“My coat?”

“To pick up the eel. I’m afraid it might bite otherwise.”

He tossed his coat to Mr Borel, who groaned and wrestled the creature out through one of the shattered window-panes.

“Good,” Arthur said. “Well. Glad I could be of service. Perhaps I should go and see what’s come in through my own windows.”

“Oh—I wouldn’t. It’s dreadful out there. Besides, you’re the only thing holding the door closed.”

“Well. Yes. That’s best. In my current state, I feel just about competent to be a door-stop.”

Wind howled and thumped at the door.

“The fellow downstairs,” Arthur said. “The typewriting business—that sign’s gone too.”

She looked up in surprise.

“Oh God. Where?”

“Halfway to the moon, for all I know.”

“I’m sorry. A silly question. God, what an awful night!”

“You know the owner, Miss… ?”

“I do. I am the owner, Mr Shaw. Or, I was, I suppose.”

Arthur was very surprised.

He introduced himself as Arthur Archibald Shaw, noted journalist for The Monthly Mammoth, and author of detective stories—aspiring, he acknowledged. J. E. Bradman—whom he’d vaguely imagined as gnarled, grey-bearded, and whiskery—turned out to be Josephine Elizabeth. She had the office downstairs, and lived in a tiny flat upstairs. She’d come down to help when she heard Sophia screaming.

“Perhaps,” Mr Borel said, “we could move a shelf to stop the door. And of course you may be guests here until this storm departs.”

They bustled about, making what repairs they could by candlelight. Sophia fell asleep somehow. Arthur and Miss Bradman talked as they worked, between interruptions from thunder and branches crashing against the window, with Borel as an odd sort of chaperone.

They talked about detective stories while they picked up and dusted off Borel’s jars of ointment. She seemed to have some very distinct ideas about how a detective story ought to go, though Arthur wasn’t sure he followed everything she said. Blow to the head, perhaps. He wondered if she were a literary type herself—this being Bloomsbury, after all. After some cajoling, she confessed that she was a poet. “But not for a while. One can’t find the time.”

“Time,” he agreed. “Time and money!”

She glanced sadly at the window. “That sign was practically new! And awfully expensive.”

“Typing, it used to say, if I recall. I suppose that means—I don’t know—document Wills? That sort of thing?”

“From time to time.”

He helped Borel heave a shelf upright. “And you do translation, of course. French? Italian? Russian? I came here from the Reading Room, if it’s still standing—one hears every sort of language around there…”

“Greek; Latin.”

“Scholarly monographs, that sort of thing?”

“In a manner of speaking,” she said, and busied herself arranging the magazines.

“A manner of speaking?”

She turned back to him. “You promise you won’t think it odd?”

“Tonight, Miss Bradman, nothing could seem odd.”

“In the safe downstairs I currently have a half-typed treatise on the Electric Radiance by a Lincoln’s Inn barrister; a monograph on Egyptian burial rites by a clerk for the Metropolitan Railway Company, who wants the whole thing translated into Latin so as to be kept obscure from rival magicians; and an account of a telepathic visit to Tibet by a—well, I shouldn’t say more. She’s been in the newspapers. An actress.”

“Good Lord.”

“You do think it odd. I knew you would. I’m telling you this in confidence, Mr Shaw.”

“Of course.”

“The thing about—about that sort of person, Mr Shaw, is that he or she will quite often pay very well for a certain… trust. Confidence. A kindred spirit. Anonymity. And Greek and Latin, of course. I have a certain reputation.”

She went to calm Sophia, who’d woken in a panic at the sound of thunder. Arthur watched her with a certain amazement.

“How does one get into that line of work?”

“Accident, I suppose.”

“Accident?”

“Most things in life are, aren’t they? May I ask how you came to be writing about science for the Mammoth?”

“My uncle, to be frank. Old George—”

Outside there was a terrible crash, possibly a tree falling. Sophia shrieked. Mr Borel told her to go and make coffee. At the prospect of hot coffee, Arthur lost his train of thought.

“The accident,” Miss Bradman said, a little later, as they stood around the stove.

“Yes? Please, do tell me.”

She took a deep breath. “It was after I came to London, though not long after. My father, having left me a little money for an education—he was the rector in a little village you’ve never heard of, but forward-thinking, and he believed in education. Anyway, after Cambridge there was a little left over for a typewriter, though hardly a room to put it in; and for enrollment in the Breckenridge School for Typewriting and Stenography. From whose dingy and dismal premises I stepped out one bright spring afternoon to see a silver-haired lady of dignified appearance staring into the window and weeping. Naturally I asked if I could help her.”

“Naturally.”

“As it turned out, her name was Mrs Esther Sedgley, and her husband was just lately deceased. From time to time she suffered what you might call memories, or you might call visions—I don’t know—she herself was never sure what to call them. The sight of her reflection in a window might bring them on, or a flight of pigeons, or all sorts of things. It reminded me of—well, now I’m wandering off from my story, aren’t I? You must tell me if I do it again, Mr Shaw. By this time we’d already moved to Mrs Sedgley’s parlour, and then she invited me to dinner, which I was certainly in no position to refuse. We quickly became friends.”

Miss Bradman sipped her coffee.

“Her husband had been a barrister—quite a good one, I think, though of course I wouldn’t know—but also the Master of a… well, a sort of society, a club for discussion of spiritual matters, and the esoteric sciences, and so on. And so after the poor fellow died, my friend had found herself presented with a bewildering array of mediums offering to call him up by spirit-trumpet, or table-rapping, or what-have-you… So that summer she engaged in travel all across London, and she was lonely. Besides, she needed a secretary, and a witness, because she considered it her business to sniff out fraud and imposture and nonsense. And so Mrs Sedgley and I went to Bromley to see Mrs Hutton’s spirit-trumpet.”

“Good Lord,” Arthur said.

“And we saw Mrs Gully turn water into rose-water in Spitalfields, and Mr H. C. Hall lift a spoon by animal magnetism in St. John’s Wood. And together we attended the re-launch of the Occult Review where Miss MacPhail—the actress—said that we were all Exemplars of the SuperMan. Though of course I’m sure she says that to everyone. I saw Brigadier MacKenzie fail to levitate, and I saw Mr Wallace’s spirits play the piano. A lot of those sort of people come to the meetings of Mrs Sedgley’s society, for which Mrs Sedgley employs me to take the minutes. And in the course of all that I suppose I earned a certain reputation. The Brigadier had a monograph he wanted typed, and Miss MacPhail wanted to learn Greek—and so on, and so on. And so—since you ask, Mr Shaw—it’s because of that chance meeting that I fell into that sort of company; and it’s because of that that I came to be here—renting the office downstairs, that is, and the room upstairs. Aren’t chance meetings terribly important, don’t you think?”

“Did the spirits really play the piano?” Sophia said.

“A good trick if they did,” Arthur said. “A good trick either way.”

“I don’t know. I will say this: that for every fraud I have met, I have met a dozen sincere and intelligent seekers after truth. After all, isn’t it nearly the twentieth century? And is it more outlandish, Mr Shaw, that there should be revolutionary advances in the science of telepathy, or clairvoyance, than that there should be electric lighting, or telephones?”

“I won’t deny that,” Arthur said.

Miss Bradman stared down at the hem of her skirt, which was soaking wet. “I’ve said altogether too much, haven’t I? You let me talk too much, Mr Shaw; you should have said something. I don’t know quite what’s got into me. It must be the storm.”

After a while Mr Borel found some relatively dry playing cards and the four of them played whist by candlelight. They were by that time all quite merry, in the way of people who’ve survived the worst of things and have nothing to do for the time being but wait. Every time lightning flashed they cheered—even Mr Borel. God knows what the hour was. Already Arthur felt as if he’d known Miss Bradman all his life.

By chance their hands touched across the table, and there was a sensation that Arthur would later swear was a sort of electric shock. The candle flickered. Something lurched inside Arthur, too, at the thought of how big London was, and how many people were in it; and at the thought of how fast the world moved, whirling through the dark, and how improbable and uncanny it was that any two people should ever, under any circumstances, meet—and that they should then find themselves talking to each other, and playing cards around a table, as if it were all perfectly normal.

Miss Bradman flushed red and drew back her hand. She went to the window and peered out into the dark.

The Revolutions © Felix Gilman, 2014

It’ll be interesting to find out if the Chesterton pastiche? references? continue throughout, or what Gilman does with them.